Managing psychosocial safety risk for a positive culture

- Glenda Devlin

- Jul 19, 2023

- 5 min read

Employers across Australia are on notice to effectively manage psychosocial safety risk in the workplace. I wonder if organisational leaders also see the opportunity for psychosocial safety to support the robust conversations necessary for positive cultures.

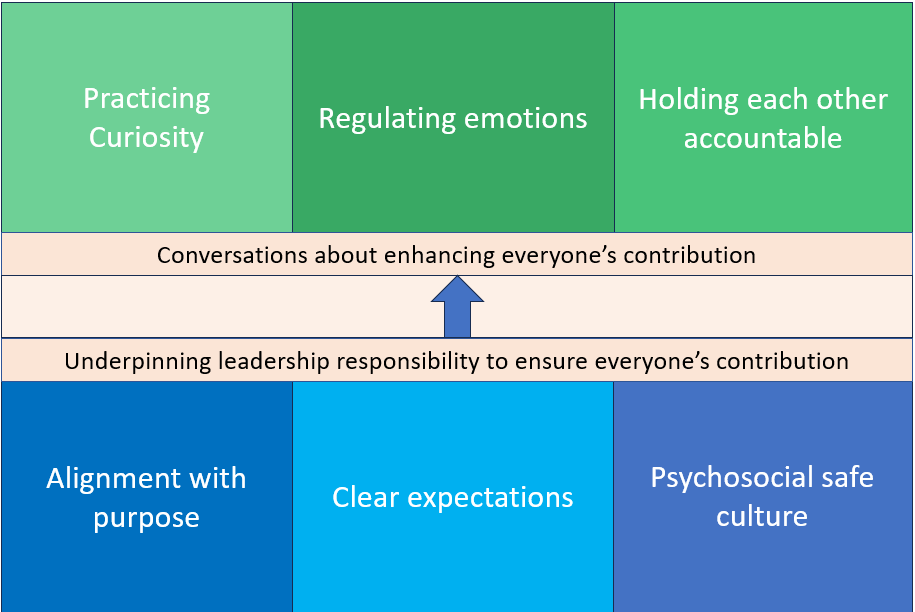

Cognitive neuroscience tells us that our brain is likely to run quickly towards managing risk and threat and walk slowly towards positive outcomes. For organisations seeking to mitigate psychosocial safety risk, it is important to recognise that attention to the threat will paradoxically, reduce attention on building a positive culture. However, smart leaders will see the opportunity to manage psychosocial safety risk and build positive culture together. I suggest that this requires driving improvements in psychosocial safety across three interconnected elements: policies and processes; robust conversations; and positive habit activation.

Figure 1: Building a positive culture while managing psychosocial safety risk.

1. Develop required psychosocial safety processes and systems with a positive culture in mind.

It is clear employers need to better manage the risk, with increasing numbers of psychosocial claims and psychological injuries generally taking more time and needing more resources to resolve (Workers’ compensation for psychological injuries | Safe Work Australia). Better managing psychological health and safety risk is a worldwide issue, with new international guidelines published by ISO (ISO 45003) in 2021, and Australian guidelines in July 2022, model code of practice managing psychosocial hazards at work (safeworkaustralia.gov.au). Every state in Australia has or is in the process of updating their WHS regulations to reflect the Australian code of practice. For example, in October 2022 the Work Health and Safety Regulation (NSW) was amended to make it a requirement for NSW employers to manage psychosocial risks in the workplace and implement control measures as they would other risks to safety.

The new standards recognise that all jobs are likely to involve psychosocial hazards. The impetus for the new regulation is to minimise harm caused by psychosocial safety hazards by monitoring the impact of job characteristics, such as workload, supervisor support and exposure to traumatic events. In addition, processes need to be in place to prevent harmful behaviours such as bullying, harassment, and aggressive behaviour. This includes the requirement to have processes to identify psychosocial hazards, assess psychosocial risks, implement control measures, and regularly review the success of control measures. The Code-of-Practice_Managing-psychosocial-hazards.pdf (nsw.gov.au) provides helpful detailed guidance for employers.

Ideally, employers will also consider how the required processes and organisational training reinforce and affirm a positive culture. For example, teams could report regularly on evidence of three areas of strengths and one area for improvement in psychosocial safe behaviours thus driving both focus on the positive behaviours and accountability for improvement.

2. Support robust conversations about performance and psychosocial safety, ensuring leaders understand how to be open and responsive to feedback.

Psychosocial safety requires more than policy and process, it requires leaders to model behaviours of listening and responding helpfully to information from staff about organisational culture and work challenges. Implementing processes, systems and training helps teams better understand expectations and requirements and clarify accountability. However, if it’s not safe for a worker to speak up about their concerns, the processes alone will not be enough.

Since 2019 I’ve been talking with teams about the nature and quality of team interactions that improve outcomes, drawing strongly on the work of Amy Edmondson, Psychological Safety – Amy C. Edmondson (amycedmondson.com), Patrick Lencioni Teamwork 5 Dysfunctions | The Table Group and Brene Brown Dare to Lead Hub - Brené Brown (brenebrown.com). There will not be robust conversations about psychosocial safety and work challenges when people in teams feel under threat (psychologically unsafe) because they believe that their concerns will be minimised, or they will be humiliated for asking a question. Workplaces need to facilitate the conditions, not just processes, to have robust conversations to enable teams to access all available information from their members and succeed. This requires leaders to step up in the way they clarify expectations as well as their openness and responsiveness to information. As a first step leaders need to speak up about the value of psychosocial safety for supporting robust cultures, not just minimising risk.

When I talk about psychosocial safety lots of people roll their eyes and say things like: “The last thing we need is more niceness around here. When we are nice, people avoid responsibility. We need people to be more accountable and do a better job”. We have all seen people use ‘niceness’ as an excuse for avoiding the hard conversations. As Kim Scott says in Radical Candor, if we genuinely care about people, and outcomes, we are motivated to speak up (https://www.radicalcandor.com/what-is-radical-candor/). However, the big challenge is what happens when I speak up. How do people engage with me? Do my leaders listen? A positive culture of psychosocial safety provides the ground for robust conversations, enabling more honest feedback about outcome performance and how well we are engaging with each other so we can keep growing together.

3. Develop an organisational approach to positive habit formation.

So, you have the policies and procedures in place and leaders are supporting teams to have robust conversations in which difficult issues can be raised. The final piece is to put in place the habits that support a psychosocially safe organisation. Habits that you want everyone to be using every day.

One of the most important habits we need to consider is how we begin and end meetings so that everyone is fully present. Most of us are operating in an environment of high distraction and many of us have forgotten how to focus. Research from Harvard University suggests we are not present in the moment about 50% of the time, KILLINGSWORTH & GILBERT (2010).pdf (harvard.edu). If we are not fully present, we are not really listening. To have psychosocial safety we need to be listening well. If organisations create habits to help people be fully present our meetings should be shorter and much more focussed and important issues will not be missed. How would it be in your organisation if every meeting started with: “phones on silent and turned over, write down anything that’s distracting you right now … is everyone with me?” Depending on the mood, meeting purpose, attendees and time of day, I like to add in an opportunity to take two deep breaths or have someone to share a short joke of the day or have one person sharing an inspiring goal or thought. We can make these kinds of small changes that make big differences to how well people listen and engage.

There are some great resources around habit formation (Habits Guide: How to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones (jamesclear.com), Charles Duhigg: New York Times Best-Selling Author of Smarter Faster Better and The Power of Habit) This is worthy of a separate blog.

The take home message: Managing organisational psychosocial safety risk will be much more successful if it’s part of a plan to build a psychosocial safe culture through processes, robust conversations and positive habits.

www.changecollaborations.com.au

Comments