What I have learnt about helping people speak up in teams.

- Glenda Devlin

- Sep 6, 2023

- 7 min read

Senior leaders are telling me that they are working hard to create psychosocial safe teams, but people are still not speaking up about their concerns. This blog outlines a model I have developed for making sense of people’s choice not to speak up and understanding how best to focus our energies and attention to make a difference.

I am passionate about helping people to have a voice so that they can contribute passionately and effectively to making good happen. Over the last ten years I have learnt a lot from great thinkers in this area, as below, and the many people who have collaborated with me in addressing the challenge of enabling people to use their voices well in the real-life contexts of work.

As an experienced leader, I have found it helpful to have frameworks help me hold the complexity of staff management. Leaders in organisations and teams are accountable for the culture that both supports people and challenges them to contribute effectively. This includes expecting everyone to listen well and be curious about other’s points of view. We could picture this as leaders providing the bus, but staff need to get on board and help others get on board.

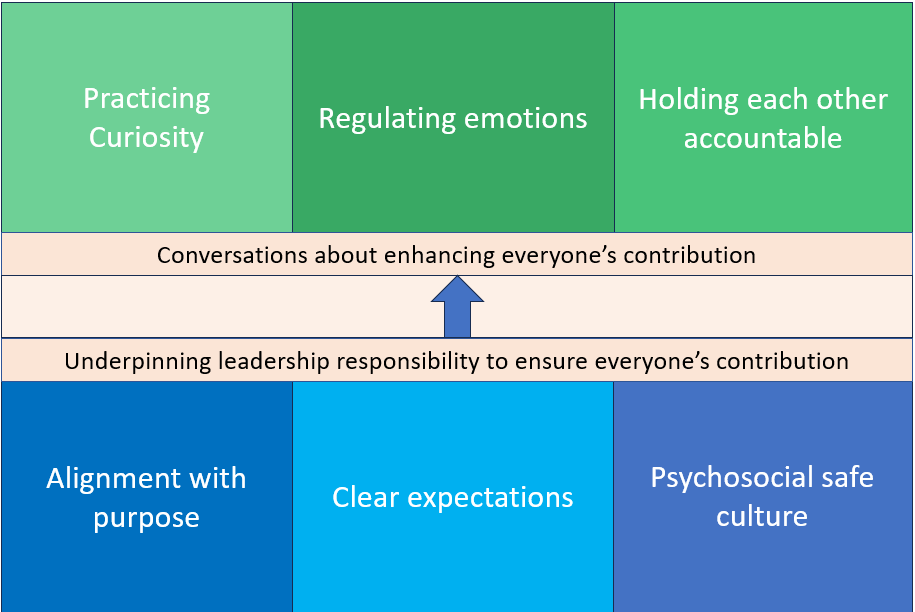

The rest of this paper outlines a framework for supporting people in teams to contribute effectively. It proposes three foundational responsibilities for leaders and three suggestions for discussion with teams. The three foundational responsibilities are alignment with purpose, providing clear expectations about engagement and ensuring a psychosocial safe culture. The three proposed areas for discussion with teams are practicing curiosity, regulating emotions, and holding each other accountable.

Three foundational responsibilities

The main point of this paper is why people don’t speak up, even when leaders have established the culture in which you would expect this to happen. However, the following are three important foundational responsibilities that require ongoing, active leadership engagement.

1. ALIGNMENT WITH PURPOSE

Leaders are responsible for hiring people who are aligned with the organisation’s goals and are passionate about the work to be accomplished. Speaking up can take courage when there is any indication that others may not agree or if what you are planning to say may lead to people feeling frustrated at losing forward momentum. Leaders have a key role in helping people to see the importance of the team’s goals, so they are willing to take risks in sharing their point of view. Team members need a reason to speak up.

2. CLEAR EXPECTATIONS

Leaders are responsible for ensuring staff are clear about how they are expected to contribute their point of view. In the teams I have led it has been my practice to have explicit group agreements on sharing the air space, so there is room for different voices and points of view, as well as clarity about how decisions get landed. These agreements are important because they ensure everyone is on the same page and because they support ongoing conversations about how to keep on improving the team’s conversations and processes. Team members need to know how they can best contribute.

3. PSYCHOSOCIAL SAFE CULTURE

Leaders are responsible for ensuring a psychosocial safe culture that rewards rather than punishes people for giving feedback or alternative points of view. As Professor Amy C. Edmondson (amycedmondson.com) has helpfully pointed out, if we want to hear new ideas, solutions, and different perspectives we need to ensure that our culture does not “suppress, silence, ridicule or intimidate” people. I use the term psychosocial safety rather than psychological safety because of the connection between the individual and social behaviours in teams and within the organisation’s context. Team members need to experience respect from their leaders and team members when they contribute.

Psychosocial safety is firstly a leader’s responsibility because of their position of power. Julie Diamond (Power intelligence - Diamond Leadership) very helpfully outlines the risks leaders face when they do not recognise the impact of their power in relationships at work. Even when leader’s intention is to support and encourage, there is always a high probability that staff will experience a sense of threat in interactions, particularly if leaders are not aware of how others are experiencing them. I provide some ideas for exploring this issue with teams in the section on managing emotional reactivity below.

So, assuming leaders reading this blog are all over these foundational responsibilities, why are people still not speaking up. What follows are three questions and practical ideas to consider with your teams to support everyone to be active contributors.

Question 1: HOW ARE WE PRACTICING CURIOSITY?

If we want to hear different points of view, we need to practice curiosity. In my experience, enhancing curiosity changes culture and is an important part of enabling collaboration on our agreed goals.

Most teams will benefit from conversations about how to enhance curiosity in meetings. Has your team had a conversation recently about the value of practicing curiosity and listening? Have your team considered the barriers to curiosity and listening? These are bedrock behaviours for ensuring positive team relationships and supporting alternative points of view, that most people agree to in principle but don’t practice enough.

For example, how often do we ask the following questions or make the following statements?

Does anyone have a different view or concerns about the ideas on the table?

Is there any other perspective on this issue or problem we haven’t considered?

I’d like to hear more from people who haven’t yet contributed.

I’m interested in hearing about how you came to that conclusion.

I’d like to hear more about why we are OK with the solution on the table.

Do you experiment with other ways to invite curiosity? Here are some activities I have found helpful in team discussions:

Identify two (likely) polarities on an issue the team is considering and allocate people to a discussion group on the priorities they are least aligned to. This is often experienced as a safer way to experiment with disagreement and perspective taking.

Ask everyone to write down the most important thing they need to say on an issue before speaking, thus acknowledging the thinking time people need and helping external processors to summarise.

Use coloured response cards when making decisions (green, red, and amber) to check in with people quickly on whether everyone agrees. This is a helpful way of normalizing different perspectives and supporting outliers to have a voice.

Inviting overstatement of positions can also be useful. For example: “I want to hear the extreme version of bad that could happen here.”

Question 2: HOW WELL ARE WE MANAGING OUR EMOTIONAL REACTIVITY?

Neuroscience helps us understand that we are wired to give positive messages little attention and to be very sensitive to threat and ruminate on difficult situations or perceived failures. People experiencing threat are not going to operate at their best and there is a lot of potential to experience threat in the workplace where our performance is under scrutiny by ourselves and others. To support people at work to perform at their best and enjoy work, leaders need to recognise the potential for everyone to experience threat and to have strategies in place to support themselves and others to take responsibility to notice and manage emotional reactivity. The point I am making here is acknowledge and manage.

When we recognise the ever- present potential for the experience of threat and our interested in managing this well, curiosity can be a very useful tool.

Do you and your team understand how threat impacts on our capacity to think clearly and respond helpfully? Do you and your team understand how to recognise threat in yourself and others? Do you and your team have skills in managing your own threat responses and engaging helpfully with others when threat is present? We can have unrealistic expectations that professional, experienced leaders have all this under their belt. The reality is that we need to be lifelong learners in acknowledging and best managing our emotions in ourselves and others.

In my leadership journey, working with my team to understand and better manage threat was a major breakthrough in building trust and increasing the positivity in the room.

Question 3: HOW ARE WE HOLDING EACH OTHER ACCOUNTABLE?

Ultimately, we need to hold people accountable to the clearly explained expectation of contributing their point of view and concerns. The leader can do everything possible and still some people may choose not to voice their concerns or contribute their perspective.

It is important that leaders engage appropriately with team members who are either not contributing or who are not listening or interested in others’ points of views. In an individual conversation leaders have an opportunity to demonstrate curiosity and invite feedback and discussion about anything they can do (or not do) to enhance the team member’s capacity to contribute effectively.

In my experience, the gold standard is when the team is holding everyone accountable to contribute. What are the questions you could be regularly asking your team to help build an understanding of high functioning teams? For example:

How are we holding each other accountable and how well is this working? Are there other ways we could do this?

Am I willing to ask my team members for feedback about how I operate in the team? How could I set up this up to be most helpful?

Are there other ways of contributing ideas or concerns that could make us more effective? How might we all take responsibility for bringing ideas on improving team interactions to the table. For example, suggesting books, articles, podcasts, or TED talks to discuss.

FINALLY, A NOTE ON CONTEXT

Speaking up in some contexts is just going to be more challenging than others. This may be about the time of day, what is happening in someone’s life outside work, the nature of the issue, and (explicit and implicit) messages about what is important or needed at this time.

Being curious about the impact of context can provide some important information on how best to respond when the level of contribution is a concern. How do you engage your team or individuals about the level of contribution when it is lagging? This may as simple as noting that energy in the room seems low.

NEXT STEPS

I encourage you to consider how you can allocate time in your team to be curious about what will help everyone to speak up and contribute helpfully to making good happen.

I’d love to have a conversation with you on this issue. Feel free to contact me at glenda.devlin@changecollaborations.com.au

Brilliant thanks Glenda. So much to learn here!